DOUBLE SEVENTH FESTIVAL or 七(Qī)夕(Xì)七(Qī)巧(Qiǎo)如(Rú)意(Yì)果(Guǒ) (V, GF)

The story of “the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl” was selected as one of China's Four Great Folktales by the "Folklore Movement" in the 1920s — the others being the Legend of the White Snake, Lady Meng Jiang, and Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai. Though the main plot of each Great Folktale is a love story individually, “the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl” is distinguished from others by its clear indication of date (the seventh day of the seventh lunar month). While the story of “the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl” roots in ancient Chinese people’s worship of natural celestial phenomena, the genesis and the transformation of its lore and traditions epitomise the close relationship between astronomy and agricultural activities in ancient China, as well as the conflation of regional cultures as southern and eastern mountainous or coastal borderlands were included into the culture of the Central Plain (中原文化).

QIQIAO LOCK CHARM RICE COOKIE or 七(Qī)巧(Qiǎo)如(Rú)意(Yì)果(Guǒ)

Double Seventh Festival or Qixi Festival falls on 14th August in 2021. To add more fun to this, Chef Jing is excited to showcase her vegan and gluten-free sweets - Qiqiao Lock Charm Rice Cookie or Qiao Guo, drawing on several old-fashioned recipes along with her own interpretation. The cookies are made from rice flour and ground sesame, thus have a sandy, smooth and delectable texture. They disappear as soon as they hit the mouth, with the delightful and delicate aroma of jasmine and globe amaranth; the addition of Longjing tea leaves helps keep a subtle balance, so that the nutty sesame won’t be too dominant. Longjing tea may have some bitterness, but the following sweet aftertaste and the long finish is redolent of deep, wholehearted love; in China, fair jasmine symbolises innocence and purity, globe amaranth eternity.

Chef Jing’s Qiao Guo looks like a piece of blue-and-white porcelain lock charm. As an amulet, Chinese lock charms are decorated with characters and symbols, meaning to protect the wearers from harm, misfortune, and evil spirits, and to bless them with good luck, longevity, namely to “lock” them to their dearests. Couples in love also hang a pair of locks with their names on a tree in Buddhist or Taoist temples, wishing not to be separated. The azure-sapphire colour contributed by butterfly pea and the pearl white compose a miniature of the night sky, “Clouds float like works of art / Stars shoot with grief at heart /Across the Silver River the Cowherd meets the Weaving Maid.” (「纤雲弄巧,飛星傳恨,銀漢迢迢暗渡。」from Immortals at the Magpie Bridge [《鵲橋仙》] by Qin Guan [秦觀, 1049–1100], Xu Yuanchong trans.). These edible lock charms can be served with limited special Galaxy Night tea blend ( butterfly pea flower, verbena, and calendula ) from our beloved local tea shop Teaism DC since 1996 . This special blend emerges tea color represnting the lovely galaxy night and it will turn purplish blue if adding a drop or two lemon juice.

THE WORSHIP OF THE STAR OF THE WEAVING GIRL

In the Central Plains (中原), the domain of ancient Chinese dynasties Xia, Shang and Zhou, the Star of the Weaving Girl is primarily associated with harvest and textiles. Besides religious elements, a pragmatic concern is that the Central Plain is characterised by four distinct seasons. Therefore, if warm clothes are supposed to be prepared by the ninth lunar month (roughly corresponding to October), women should begin to weave clothes from the seventh lunar month. It is for both ritual and practical reasons that later Qixi Festival traditions, such as “demonstrating dexterity” (斗巧) and “pleading skills” (乞巧) take shape. One of the pleading ways is to put a basin of water in the sun, then lay a needle on the surface carefully. If the shadow of the needle at the bottom of the basin turns out to be flower, star or bird-shaped, the skill is assumed to be conferred; if the shadow looks like a stick, the female worshipper fails to get the Weaver Girl’s promise. Another way is a needle threading competition under moonlight: the first one who makes it through wins the Weaver Girl’s favour.

In southern China, especially Guangdong, and Fujian, where climate is beautiful and warm all year round, Qixi Festival is assigned to be the birthday(s) of the Seven Star Goddess(es) (七星娘娘, also “the Seven Goddesses of the Maidens” [七娘媽]). The southern Chinese people believe that the Seven Star Goddesses are the six elder sisters of the Weaving Girl, who pity the two children separated from their mother. Given the grave risks of infant and child mortality, the Seven Goddesses are the guardians of children, particularly little girls, protecting them until 16 years old (adulthood). On the Qixi Festival, while parents ask the Seven Goddesses to be the godmother of their newborns, girls reach maturity take off the blessed medallion or amulet.

Needless to say, the Star of the Weaving Girl, resembling either the Weaving Girl exclusively or the seven sisters, is worshipped as the protector of marriage and true love all over China and several countries in East Asia. It should be noted that the Qixi Festival in ancient China was first and foremost celebrated as Women’s Day, married and unmarried, whilst the “Valentine’s Day” was the Lantern Festival (15th of the first lunar month; in southwest China also “Shangsi Fesitval,” celebrated on the third day of the third lunar month) when the moon is brightest and fullest in a year. On the day of Qixi, maidens’ prayers to the goddess(es) for a good husband and a happy life involves the display of their needlework and tables of offerings: tea, nuts, dried and fresh fruits, and a special dessert called Qiao Guo (巧果, “cake of skillfulness”). The recipe of the festive dessert varies across China: in central and northern China, Qiao Guo is a nut-based cake made with moulds of different shapes; for residents along the eastern coastline (Shanghai, Hangzhou etc.), Qiao Guo is a kind of twisted doughnut or fried thin pastry in moulded shapes; still, the Cantonese, Hokkien and Taiwanese version is a bite-size sticky bun made from fried rice flour and glutinous flour, its concave shape is used for holding the tears of the Weaving Girl.

THE WISDOM OF CHINESE ASTRONOMY

One of the brightest stars in the night sky is Vega in the northern celestial hemisphere. It belongs to the constellation of Lyra, representing the lyre of Orpheus in Greek mythology. Orpheus attempts to retrieve his wife Eurydice from the underworld, and his music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone. Interestingly, Vega, known as the Star of the Weaving Girl (織女星; the astronomy term is “the First Star of Weaving Girl [織女一]”) among Chinese people, is also associated with unfulfilled love in Chinese mythology. Look at On the other side of the Milky Way, can you find Aquila? Its brightest star Altair is known as the Cowherd Star (牛郎星) in China. The Chinese perceive these two stars as a couple separated by the “Silver River” (銀河, the Milky Way), gazing at each other. According to traditions, while Weaving Girl belongs to the Heavenly Court, the Cowherd is a temporal being, thus their love is not allowed.

As the circulation of “the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl” dates back at least to the 7th century BC, it is not hard to imagine that the tradition is unfixed, transforming through thousands of years. Among the variations, the Weaving Girl is presented as one of the daughters, granddaughters or a seamstress of the Jade Emperor (玉皇大帝, the ruler of Heaven), in charge of weaving the rosy clouds; the Cowherd is a solitary peasant who was kicked out of his poor peasant family by the obstructive wife of his elder brother. One day, the Weaving Girl descends to earth with other goddesses. When they are bathing, the Cowherd secretly hides the Weaving Girl’s magic robe on the advice of his intelligent old ox so that the Weaving Girl is left in the stream while others are able to fly back to Heaven. Then the Cowherd emerges and proposes to the Weaving Girl. Tired of her life in the heavenly court, the Weaving Girl accepts his proposal. The couple lives happily and peacefully, and within three years, they have a son and a daughter. However, the Jade Emperor is furious when he heard about this, for trans-domain union (in Chinese popular religion, there are three domains in the cosmos — Heaven, Earth, and the Underworld) is prohibited. The Jade Emperor dispatches troops to escort the Weaver Girl back to Heaven by force, and as they are ascending, the Cowherd puts on a pair of magic boots made of leather from his late ox, carrying his son and daughter in a shoulder pole, chasing his wife. The Heavenly Troops do not expect a mortal can deviate. As the Cowherd has almost caught up with them, the Queen Mother of the West (西王母) draws the Silver River (The Milky Way) in the sky with her golden hairpin and blocked his way. When the Cowherd can do nothing but to witness his wife being taken away and their children are crying, the couple’s love moves the magpies. Flapping side by side over the Silver River, the magpies build a bridge with their bodies for the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl to meet. The Heavenly Court is also touched, and the Jade Emperor allows this couple to meet on the Magpie Bridge once a year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month (In 2021, they will meet on 14th August).

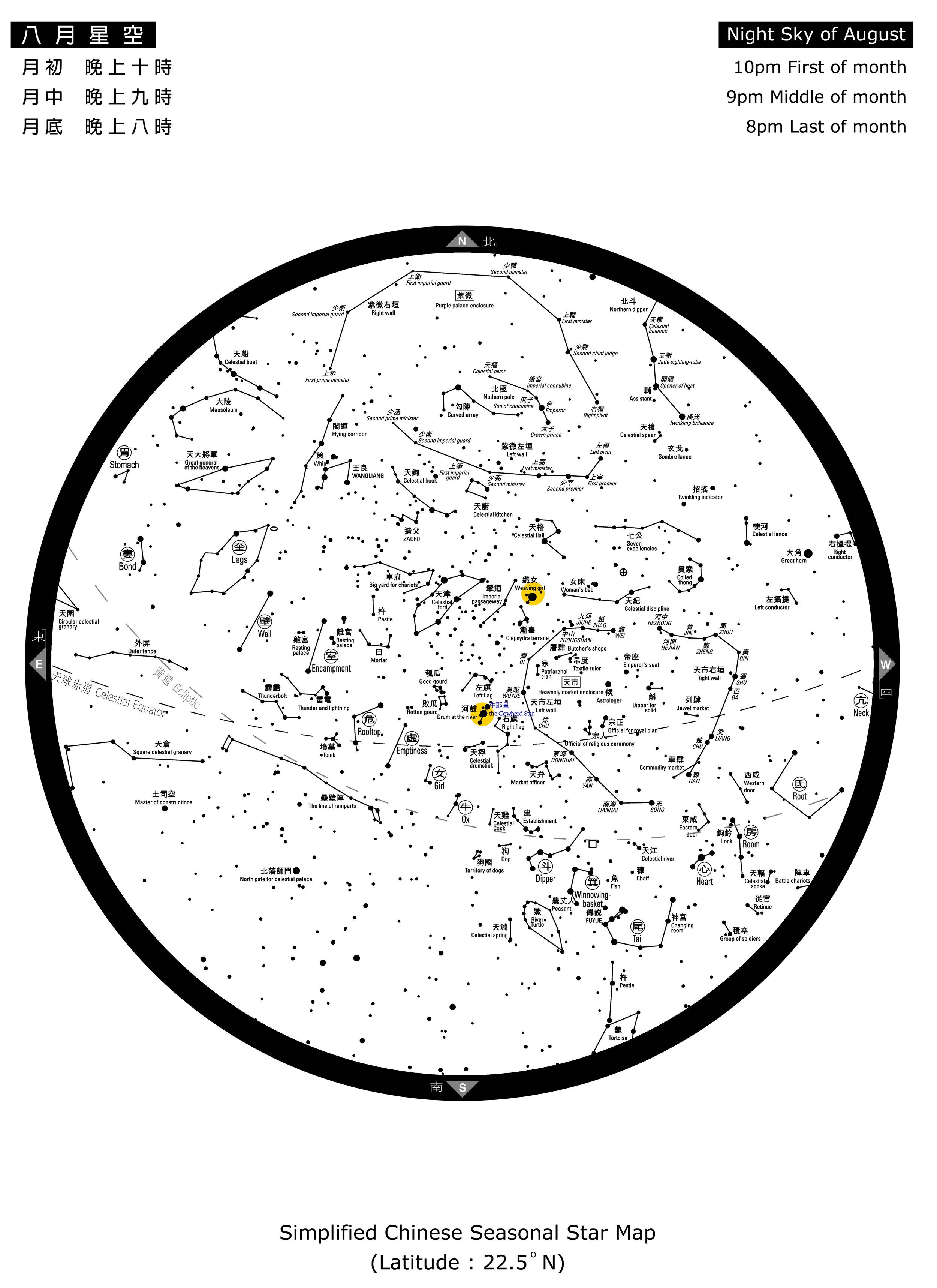

According to traditions, the Jade Emperor allows the Cowherd and the Weaving Girl to meet on the Magpie Bridge once a year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. The date is not chosen at random. Firstly, the ancient Chinese noticed that it is in the seventh lunar month of the year when the Ox mansion (牛宿, to which the Star of the Weaving Girl and the Cowherd star belong) and the Girl Mansion (女宿) both appear in the night sky: according to Book of Rites (《禮記》) edited by Confucius, the Girl Mansion culminate at dawn in the first month of summer, and the Ox Mansion culminate at dawn in the first month of autumn, as the latter is chasing the former. Furthermore, in the early and mid-seventh lunar month, the pair of the Star of the Weaving Girl (Vega) and the Cowherd Star (Altair) ascend from the east to overhead, just at night falls, as the couple does not waste one single minute reuniting once a year. (Please refer to the Summer Triangle [Vega, Deneb and Altair] season for modern explanations.)

In ancient China, one of the main purposes of astronomical observation was timekeeping and detecting the change of season so as to advise agricultural activities and rituals. Chinese people divided the celestial sphere into 28 star mansions (星宿), each consisted of several constellations. The motions of the star mansions and constellations serve as a stellar calendar. Because the emergence of Ox Mansion is expected in the eighth lunar month, and ox is the most important animal for an agrarian society, the eighth lunar month isthe month of worship, the preceding month is dedicated to the preparation of rites. In Book of Rites (《禮記》), it is also noted that “In the third month of summer…Gentle winds begin to blow… In this month, orders are given to the four inspectors to make a great collection over all the districts of the different kinds of fodder to nourish the sacrificial victims… the officers of women’s [work], on the subject of dyeing and colourful embroidery; (they are to see) that the gorgeous patterns all according to the ancient regulations.” (「季夏之月……溫風始至……是月也,命四監大合百縣之秩芻,以養犧牲……是月也,命婦官染采,黼黻文章,必以法故,無或差貸.」For full text of Book of Rites in English, see The Lî Kî, James Legge trans., 1885.) But, when does the third month of summer begin? It is the appearance of the Star of the Weaving Girl at dusk in the east that signifies the conclusion of summertime, which is acknowledged as early as in the Xia Dynasty (21st-16th century BC) , “In the seventh month … the Weaving Girl is right in the east.”(「七月……初昏織女正東鄉.」 — Xia Xiao Zheng 《夏小正》, The Small Calendar of the Xia).

Blog prepared and edited by Yuxuan Cai

History Ph.D Candidate at University of Cambridge